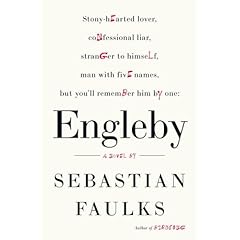

Engleby

By Sebastian Faulks

By Sebastian Faulks

ISBN: 978-0-385-52405-6

$24.95

“I decided not to be mad any more; I was never going back to a place like that again.”

Engleby, pg. 191

$24.95

“I decided not to be mad any more; I was never going back to a place like that again.”

Engleby, pg. 191

Audiences love underdogs and surprises. They also love the formulaic nature of entertainment. Readers, even if they’ve never encountered the term “archetype,” recognize signature character types when they see them. Conventional literary signposts clue readers in on who to root for, who the good guys are, and who should be wearing the black hat. In Engleby, Sebastian Faulks turns conventional character development on its ear and, like Nabokov did with Humbert Humbert in Lolita, forces the audience to invest in a protagonist who is detestable, yet addictive.

By no means is Engleby merely a case study of a sociopath. Michael Engleby’s very thought process is intellectually elitist, condescending, and uncomfortably devoid of recognizable emotion. On page 2, he gives readers cause to question his own understanding of the world’s events. Because of the journal format of Engleby the protagonist is already set up as an unreliable narrator, but his intelligence and astuteness cause audiences to question the traditional literary device. Even still, through each analysis Engleby reveals regarding society and social practices in general, a clearer understanding of his anti-social mentality is gained. Engleby hovers on the fringe of social groups and is apt to point out that he likes “to be invisible.” At one point he invites himself to the country with a group of students working on an independent film to be close to Jennifer Arkland, and while no one can remember who invited him to begin with, they’re grateful for his cooking and drug supply. Other times he relives, in painful detail, the various abuses he sustains from countless others—both university dons and his fellow students at each of the schools he attends.

Though readers may sympathize with some of Engleby’s experiences and insights, there are equally as many instances for the reader to turn on him. The sharp disconnect between his intellectual understanding of the world and social interaction, and the practice of those skills and application of that knowledge, is the single most unsettling aspect in his character. You don’t like Engleby, but you want to understand him. You’re compelled to understand him. Through the entire journal you wait for some inkling of genuine emotion, for some signal that he hasn’t fully detached from society and reality, or that he is still, in some basic way, human. Faulks engineers this pseudo-diary in such a captivating way that the readers become co-conspirators with Engleby, and even to the very end, reserve a fraction of hope for the troubled young man.

Plenty of people have experiences or demonstrated the anti-social and intellectual superiority complexes that Engleby goes through, but not every one is Engleby. Not all intellectual elitists are certifiable. Not all highly intelligent people exist solely in the landscape of their own minds. Because Engleby had never experienced the guiding hand of a true teacher (he felt, and probably was, smarter than the “dons” at his various schools, including Cambridge). He stepped into the tiger pits of philosophy and sociology with no hand to help him back out into reality. His existential crisis is not merely a phase, but becomes a disease of the mind.

Engleby could be a treatise on the mind of a single mentally ill young man, but it shines a light on issues that are far more complicated. It’s about the lack of perception of those around troubled individuals, and it can easily be a warning to society about the dangers of closing your eyes to bullying—specifically bullying based on a warped sense of tradition or “boys will be boys” attitudes. Most importantly, Engleby speaks to the dangers of knowledge and unguided intelligence, and the dangerous line in the sand between intelligence and insanity.

The last third of the book shifts perspective from the Engleby readers know, to a medicated, institutionalized Engleby who can identify his behavioral problems of the past and the crimes he committed, but still cannot feel appropriate emotional responses. The difference is that he wants to. While others may criticize this turn in the novel, it is absolutely necessary to complete the story. To leave the journal incomplete, or to shift to third person would render the tragedy in Engleby trite and meaningless. Without his shift from book knowledge to personal knowledge, his experiences and writings would be rendered pointless because even after he is given the tools to help himself, Engleby chooses to remain locked in the safety of his own mind where he can rearrange reality and history, and that itself is his tragedy.

Faulks departed from his comfortable writing styles with Engleby, and readers may or may not be appreciative of the sudden shift in gears. He moves from his comfort zone of historical fiction to a fiction riddled with history and both mental and social illness in such a way that reading the novel once would cheat readers out of the carefully woven clues and allusions Faulks works into his writing that are only able to be appreciated after the final revelations of the protagonist. Engleby may be a departure from Faulk’s other writings, but it is a path well following him down.

By no means is Engleby merely a case study of a sociopath. Michael Engleby’s very thought process is intellectually elitist, condescending, and uncomfortably devoid of recognizable emotion. On page 2, he gives readers cause to question his own understanding of the world’s events. Because of the journal format of Engleby the protagonist is already set up as an unreliable narrator, but his intelligence and astuteness cause audiences to question the traditional literary device. Even still, through each analysis Engleby reveals regarding society and social practices in general, a clearer understanding of his anti-social mentality is gained. Engleby hovers on the fringe of social groups and is apt to point out that he likes “to be invisible.” At one point he invites himself to the country with a group of students working on an independent film to be close to Jennifer Arkland, and while no one can remember who invited him to begin with, they’re grateful for his cooking and drug supply. Other times he relives, in painful detail, the various abuses he sustains from countless others—both university dons and his fellow students at each of the schools he attends.

Though readers may sympathize with some of Engleby’s experiences and insights, there are equally as many instances for the reader to turn on him. The sharp disconnect between his intellectual understanding of the world and social interaction, and the practice of those skills and application of that knowledge, is the single most unsettling aspect in his character. You don’t like Engleby, but you want to understand him. You’re compelled to understand him. Through the entire journal you wait for some inkling of genuine emotion, for some signal that he hasn’t fully detached from society and reality, or that he is still, in some basic way, human. Faulks engineers this pseudo-diary in such a captivating way that the readers become co-conspirators with Engleby, and even to the very end, reserve a fraction of hope for the troubled young man.

Plenty of people have experiences or demonstrated the anti-social and intellectual superiority complexes that Engleby goes through, but not every one is Engleby. Not all intellectual elitists are certifiable. Not all highly intelligent people exist solely in the landscape of their own minds. Because Engleby had never experienced the guiding hand of a true teacher (he felt, and probably was, smarter than the “dons” at his various schools, including Cambridge). He stepped into the tiger pits of philosophy and sociology with no hand to help him back out into reality. His existential crisis is not merely a phase, but becomes a disease of the mind.

Engleby could be a treatise on the mind of a single mentally ill young man, but it shines a light on issues that are far more complicated. It’s about the lack of perception of those around troubled individuals, and it can easily be a warning to society about the dangers of closing your eyes to bullying—specifically bullying based on a warped sense of tradition or “boys will be boys” attitudes. Most importantly, Engleby speaks to the dangers of knowledge and unguided intelligence, and the dangerous line in the sand between intelligence and insanity.

The last third of the book shifts perspective from the Engleby readers know, to a medicated, institutionalized Engleby who can identify his behavioral problems of the past and the crimes he committed, but still cannot feel appropriate emotional responses. The difference is that he wants to. While others may criticize this turn in the novel, it is absolutely necessary to complete the story. To leave the journal incomplete, or to shift to third person would render the tragedy in Engleby trite and meaningless. Without his shift from book knowledge to personal knowledge, his experiences and writings would be rendered pointless because even after he is given the tools to help himself, Engleby chooses to remain locked in the safety of his own mind where he can rearrange reality and history, and that itself is his tragedy.

Faulks departed from his comfortable writing styles with Engleby, and readers may or may not be appreciative of the sudden shift in gears. He moves from his comfort zone of historical fiction to a fiction riddled with history and both mental and social illness in such a way that reading the novel once would cheat readers out of the carefully woven clues and allusions Faulks works into his writing that are only able to be appreciated after the final revelations of the protagonist. Engleby may be a departure from Faulk’s other writings, but it is a path well following him down.

Review by Dawn Papuga

0 Comments:

Post a Comment